June 09, 2025 • 5 min read • Real Estate

Real estate has no shortage of old sayings, but the one I keep taped to my monitor is simple:

“You make your money when you buy.”

And yet, every week, our team pores through presentations painted as abstract art, with forecasts bending reality and exit cap rates defying logic. In this blog, I cover a few rules and tips to safeguard your capital as multifamily investors.

Rule 1: You Don’t Buy the Building. You Buy the Block.

“We plan to spend $14,500 per unit and increase rent roll by 30%”. — most first-time investors.

Whenever I hear that line, I smile. Then I open my “MF UW” tab, a shortcut we built for multifamily underwriting that’s always one click away. It’s a simple stack of links, but it’s saved our team from bad deals (and wasted time) more times than we can count:

- justicemap.org (income maps)

- cbb.census.gov (income/spending/median age/jobs/etc.)

- worldpopulationreview.com (population data)

- rentometer.com (rents)

- neighborhoodscout.com (crime, schools, etc.)

- Google Maps (aerial views and amenities)

The big idea: Your renter is a product of the neighborhood. Unless you own every building on the block, you’re betting on the fabric of the community to do some of the heavy lifting. Your renters will always be an output of the area you’ve invested in. Remember, pioneers get all the arrows. Don’t be the pioneer.

A few first-level filters I always consider:

- Income: What is the area income? What is the current rent:income ratio?

- On average, you do not want a household to spend more than 30% of their monthly gross income on rent. If your proforma is above 30%, it’s a bad proforma.

- Demographics: Who rents in this area? Are they students, families, elderly?

- Identify your current renter profile, and your prospective renter profile. You will likely regret mixing families with students.

- Population Trends: If people are leaving, rents are decreasing. Simple.

- Crime: Crime kills commerce. Commerce creates jobs. Jobs pay rent.

- Amenities: How close is the nearest grocery store? What’s the brand? Any parks nearby? A visit to the local grocery store will tell you everything you need to know about the neighborhood.

(Also, don’t sleep on environmental constraints. A freight train 500 feet away? That’s not a value-add. That’s a vacancy driver.)

Rule 2: Age & Unit Mix Matter.

This is where novice investors get clipped.

Older buildings often come with hidden liabilities. Plumbing, electrical systems, and roofing deserve serious scrutiny, and not just a glance during a walkthrough. Cast iron and galvanized steel pipes, standard in pre-1970s construction, degrade from the inside out. PVC, the modern replacement, offers better longevity. A sewer scope should be non-negotiable — rotted underground plumbing has a way of turning projected IRRs into wishful thinking.

In properties from the late 1880s to early 1900s, knob & tube wiring was quite common. Knob & tube wiring is known to cause safety hazards over time. In my experience, many insurers are unwilling to insure on properties with knob & tube wiring due to their perceived risk. For 1960s builds, investors are cautioned to identify the type of electrical wiring — whether copper or aluminum. Due to the increased costs of copper in the 1960s, many builders opted-in for aluminum instead of copper. Aluminum wiring is known for its fire hazards and can present challenges when securing insurance coverage.

And then there’s unit mix, a silent killer of NOI. Studios and 1-bedrooms look efficient on paper, but they bleed on turnover. Single residents pair off, have kids, and move. Every move-out is a new leasing fee, new paint job, and new carpet. 2- and 3-bed units offer higher stability and less churn. Remember, turnover is expensive and stability is wealth.

Rule 3: If You Don’t Track It, You Can’t Change It.

Our team’s strategy has been to create rubric templates in tracking important criteria for our geographic areas of consideration. Our proprietary template weighs each city or neighborhood across measurable inputs and aggregates the scores. Each input is given its own individual weighting based on its importance:

- Supply/Demand Balance

- Political (Landlord friendliness, zoning, rental control)

- Crime

- Population

- Infrastructure: water, energy, taxes

- Income

- Labor Market

- Population

- Affordability

- Natural Disasters

- City Coffers

Ratings can be attributed on macro and micro levels — from cities, zip codes, and down to specific neighborhoods. Though not perfect, it provides clarity and uncovers blind spots.

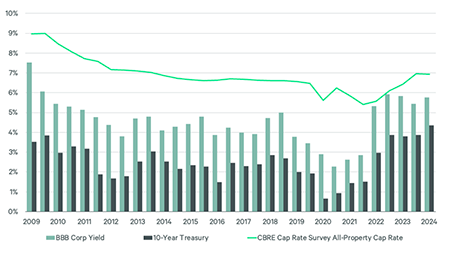

One last metric to track are credit spreads. An investor's required rate of return is mostly measured against the “risk-free rate of return,” aka the yield of the 10-year treasury. If the 10-year treasury is yielding an annualized 4%, an investor in a Class A multifamily property may require a 200 basis point (2%) spread on top of the 10-year yield, for a total required rate of return of 6%. A class C property may require 8% to compensate for the additional risk. Buy when spreads are wide. Sell when spreads compress. That’s the real art in this business.

It’s tough to condense what could be a book on multifamily investing into a blog, but these rules should help investors avoid landmines. Have rules of your own? Please share and we’ll forward to our readers!

Yieldwink

Yieldwink